Taking up the mantle for mothers and fathers striving to manage parenthood with work was borne from her own lived experience.

“I had postpartum anxiety after my first son,” recounts Lauren Smith Brody, CEO, The Fifth Trimester. ” I was at an executive level at that point. I’d moved up really quickly with the hope of having a lot of flexibility by the time I had my kids,” she told Lianne Castelino during an interview for Where Parents Talk. “And yet, I found myself really, really having a very hard time as a brand new mom.”

[et_pb_toggle admin_label=”Click for video transcription” title=”Click for video transcription” open=”off” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

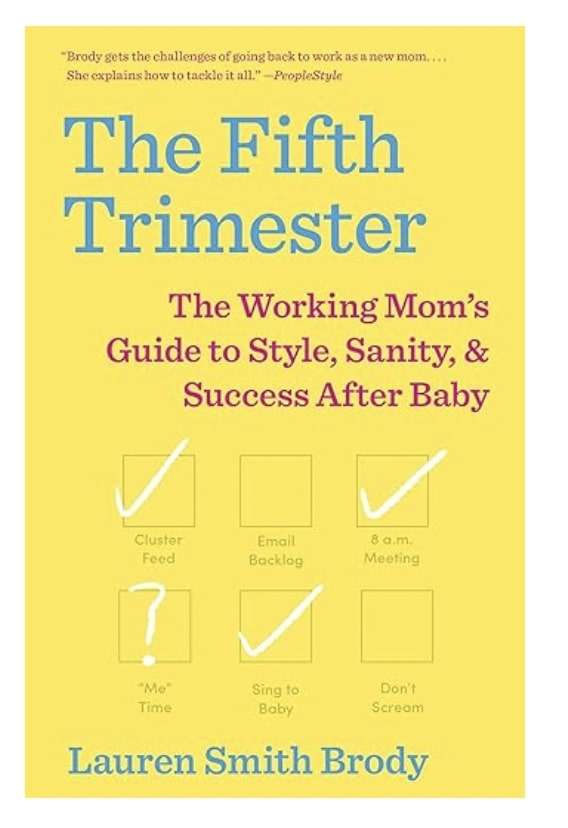

Welcome to where parents talk. My name is Lianne Castelino. Our guest today is a journalist, author and entrepreneur. Lauren Smith Brody is the CEO of the fifth trimester and co founder of chamber of mothers. She’s also a speaker and a mom of two. Lauren’s first book called The fifth trimester, the working moms Guide to Style sanity, and success after baby was published in 2017. She joins us today from New York City. Thank you so much for being here.

Thank you, Lianne. It’s such a pleasure.

Seven years now since the book first came out, and certainly lots has happened. But let’s start for people who might not be aware. What does the fifth trimester refer to?

Of course, yes. So you know what the first three are, the first three typically are pregnancy. The fourth is something that I learned about after having my first son and reading a very popular book at a time at the time called the happiest baby on the block. It was by a pediatrician named Harvey Karp, and parents these days probably know him as the guy who invented this new, he’s fantastic. And throughout the book, he introduced me to the idea of there being an additional trimester, that human babies because of the size of our heads and the size of mom’s pelvis, are born a trimester earlier developmentally than other mammals. So to sue them, you recreate the feeling of the womb with all these s verbs shushing and swaddling, and swaying and sucking for pacifier. And I just remember reading that and it was true, I had postpartum anxiety after my first son, I was at an executive level at that point, I’d moved up really quickly with the hope of having a lot of flexibility by the time I had my kids. And yet, I found myself really, really having a very hard time as a brand new mom, and his book was full of comfort. However, throughout it, he said, Just wait, Mama, just get to 12 weeks and your baby will wake up to the world and start to give something back to you and get on something of a schedule and maybe start to sleep, you know, more regular intervals. And I thought, 12 weeks, 12 weeks, the irony of that number, that was when I was going back to my job, my paid work. And I knew even then that I had it better than most American women that I was able to take those full 12 weeks. Some of them were unpaid, we could afford it, it was a stretch, but it was doable. And yet still, I got back to work. And I felt my baby was getting on something of a schedule was starting to be the baby that I thought it was going to give birth to originally. And I found that the only way I could get through it really was by being very, very transparent about what was hard about the transition. And like I said, I was at an executive level. At that point, I worked in women’s magazines, so largely with other women who were pretty comfortable talking about their physical needs emotional needs. And yet I didn’t see anyone around me really talking about parenthood, it was very much in the sort of Girlboss era of fake it till you make it, dress for the job you want not the job you have. Try, try try, just keep trying. And you’ll make it which of course didn’t account for a whole lot of factors that are much more systemic, which I didn’t realize at the time. And I had a moment when a colleague walked into my office. And she said to me, you know, we really really missed you over your maternity leave, think if we were fiddling over a layout of of a fitting a headline onto a magazine page. And she said, You know, I’m really appreciative and just thanks also for like all of this, and she’s gesturing to my desk where I have out my, my breast pump. And God knows what I looked like, I’m sure I had circles under my eyes and like some for some stay on my sweater. And, and I was a little I was embarrassed, I didn’t know what to say. And I paused. And then she continued, because you’re the only one here showing me that I can do it one day too. And you don’t make it look easy. It definitely looks hard. But you’re doing it and you’re showing up. And I know I want to be a mom one day too. I knew I want to continue with my career and thanks. And that was a real wake up call for me when I realized that although working motherhood was new to me, and it was going to continue to be hard. What I had to learn from this point out was management and, and modeling and showing that we could integrate our real lives and our real personhood into into work and still succeed. So I sort of filed that away. I had my second son a few years later, my husband was through his medical training. At that point, I had been the primary breadwinner for the first oh gosh, at least 10 years of our of our marriage. And, and I had this idea of there being a fifth trimester of that transition back to paid work after maternity leave being an additional developmental transition and trimester but not necessarily for baby but for the working parent. And that’s the idea was born. I eventually wrote my book, I surveyed and interviewed more than 700 Other moms with all kinds of definitions of what ambition looks like different kinds of careers, different family structures. To figure out that initial problem I had what was an individual problem to be solved versus perhaps a system that working together we can each play a part in helping to solve. So that launched the book. And then from there, I launched my business and started this movement. And it’s been an absolute pleasure and an honor to be able to bring individual support to people, but also to help look at bigger structures and systems and get into companies and help them do better and work in public policy and help our greater nation do better by parents.

Certainly plenty of lived experience that served as your motivation for writing this book in the first place. And you were the very demographic that the book addresses. So very interesting from that perspective. Take us, Lauren, through some of the research that in a really struck you as you poured yourself into writing this book, you talk about interviewing more than 700 women, I’m wondering if there’s anything that you saw or heard in those interviews, in particular, you’ve got really captured your attention.

Oh, absolutely, just how much of the physical experience and the mental health experience of new parenthood is, the data really does all coalesce around six months postpartum as being a real transition point. For moms, as I said, from all different kinds of backgrounds, all different kinds of circumstances to just say, actually, this is a biological need. And that’s the moment at which our bodies start to feel like our own again, not the same as they were before different, you know, of course, but but hours. And that’s when we start to get a handle on focus, and on just the emotional and mental health transitions of parenthood to and not everyone, it takes some people longer, some people come to it faster. But when I surveyed these hundreds and hundreds of women, that’s what eventually they said is that it was at about the six month mark about the six month mark, and the sleeping two, I asked understanding that the people I was talking to, were coming from all kinds of different cultural backgrounds and different definitions of like, what does a full night’s sleep look like? I didn’t ask When did babies sleep through the night? I asked at what point did you as a mom, get seven hours straight asleep. And seven hours to be clear is like not even enough for me. I wanted to use that as a very conservative standard. And it was at seven months postpartum. And so when I had sort of the validation of all these numbers that are like so far out past that 12 week mark of what FMLA covers in America, I started looking at other research that I didn’t even know about when I was going through it myself. And essentially, all of the research shows and has for 30 years, 35 years that six paid months of parental leave is the minimum that’s protective of mom’s mental health, mom’s physical health, babies physical health, dad, or partner’s bond with the baby mom’s ability not just to maintain her career, but also ultimately her income. All of it coalesces around six months. And so what that said to me is that this sample of these hundreds of women who are answering these questions, they’re pretty representative of a biological need. And it’s not to say that you can’t go back sooner than that. Obviously, most people do and have to I certainly did. But to understand that if you are back before you feel ready to be, it’s not your fault, you’re not doing anything wrong, there’s no failure, there’s no reason to feel, as I did you know, guilty when you’re back at 12 weeks, and you feel torn, it doesn’t feel right, I called it in my book, The second cutting of the umbilical cord, because that that is what it felt like to me. But that it’s a larger system, and that you deserve every ounce of support that you can ask for from your family, your community, your friends, but also your workplaces to help get you over that hump so that you can be able to stay in your career, and use what you’ve learned in that fifth trimester transition and pay it forward for others to help change systems and make progress for all.

You know, it’s so interesting, because when you look back at when this book was published back in 2017, very different time in place. Societal discourse around mental health was very different if we just pick on that component for a second. So the question then becomes Lauren, do you believe that we are more ready today, as a society in general, to have this conversation about the intersection between, you know, working parenthood and the business world?

I do. There’s a lot more research available, you know, done by me by colleagues of mine beyond beyond just this book. I also think, you know, just speaking to just the everyday mother, I think it’s really really helpful that we have a shared vocabulary now that didn’t exist then and, and I mean, terms like the fifth trimester, which I coined and made up and trademarked but that now people find community in but also things like understanding unpaid labor, you know that that term existed back then, but not a whole lot of people were using it. I think the pandemic really, really made visible, a lot of unseen unpaid labor that goes into care work that It is absolutely just as valuable, if not even more valuable than then paid work and understanding sort of the math and the balance between the two. It’s understanding terms like benevolent discrimination, which is a piece of the motherhood penalty. And I love to explain to the motherhood penalty is the measurable negative impact of motherhood on mom’s earnings, but also on her her perceived her status, but also her perceived dependability in the workplace. And one way that it shows up is in salary. And in offered starting salaries, if someone knows you’re a mother, or they perceive you as someone who might be a mother soon, so that that’s one way. But another way, is actually benevolent and is well intended. But it’s something that as a mother, you can actually help people understand how to work with you better and give you opportunities by saying, I understand that you may say, oh, let’s not ask her to go on that trip, Let’s not ask her to take on that additional client. Let’s not look, we don’t want to bother her, she’s got a new baby. And that comes from a really good place. And understanding it comes from a good place helps you negotiate around it, but to say thank you for being so considerate, I really I want the agency to be able to decide what what I can and can’t take on right now. And I I’m really good at making these new decisions and compromises. And so, you know, give me the opportunity, please. It’s that sort of sort of understanding and finding community and some of the vocabulary that we now have on the tips of our tongues in a way that we didn’t before. And it brings you together and it helps you see that this is not an individual problem. This is not you know, an evil boss situation, very few people actually have an evil boss, most bosses also are caregivers to in one way or another and want to be able to to help their employees succeed and be productive. There’s also a whole lot of new research. Some of it actually, I worked on in the last year, I wrote a white paper in partnerships was a partnership between my business, the fifth trimester and childcare company called Vivi, that’s really innovative. And they were my thought partners in it in researching the return on investment of caregiving support at work, so that the caregiving benefits so that is everything from you know, a stipend for childcare or backup childcare, that kind of thing. It’s paid leave, it’s paid Nicky leave. But it’s also things like measuring people’s output when they have more flexibility. And we did. We did 10 case studies looking at what people who were in pretty good situations, they raised their hands to be interviewed for this. That’s an important qualifier as a subset of employees to say, here’s what I used over the past year that was offered to me, here’s the you know, the backup care the the flexible spending account that I put towards my childcare bills, the you know, the the midterm maternity leave paternity leave that I was able to take, here’s what it cost my company over the past year. And here’s what it allowed me to do in terms of my output. And in putting a number to that, which by the way, is 18, it’s eight, the ROI of the ROI of caregiving benefits is 18x. So for every dollar a company spent supporting its employees with training and all of these things, they get back $18.93 and output from them like just super capitalistic way to explain it. But where I’m going with this is that we now have a lot of the economic arguments for the things that felt like they were the right thing to do the moral imperative, but that gosh, they just might not make business sense. They now make business sense. They always did. But now we have the numbers to prove it. And so I did that research, there was other research done by Boston Consulting Group, there have been a number of think tanks that have looked into various pieces of this. And again, it’s a little bit like that six month moment of coalescing of all of the data and research. It all shows the same thing, which is that when we do do the right thing for not just new moms, but all moms, all dads, anyone doing eldercare anyone who sees caregiving as a part of their identity in the work that they do, it pays off, people are more productive people are more motivated people do better work. And that whole cultural narrative shift. I’ve been really proud to be a part of, but I think that that’s what’s made the most progress that plus just the visibility that the pandemic put on a lot of these issues for for families.

Progress is certainly welcome. And as you mentioned, the pandemic really, you know, had seismic shifts on the world. But with respect to this particular topic, because I’ve interviewed other people in and around this topic, massive amount of impact, what more in your estimation needs to be done? What does success look like?

Oh, my gosh, what a great question. I mean, so I tend to I tend to lean pretty far left here, but I’ve seen I’ve seen that. Okay, let me back up. So So my work as I’ve described to you that grew out of the book is pretty much like some of its academic but some of it is very is private sector and It’s really helping people who largely I will admit to, you already have access to pretty good employment standards like they’re they work for companies that want to hire someone like me to come in and make them even better at supporting and retaining and recruiting parent employees. So pretty good people. My work was not fully reaching the people who needed them most, which is the people who in the United States are not even covered by FMLA. So that’s about half of our country, the people who have access to No Child Care, because 51% of America is considered a child care desert. And so I’ve now co founded with a bunch of other amazing women, the Chamber of mothers, which does public policy work to reach really universally everyone. So what success looks like, in my estimation, is progress in the private sector and progress in public policy happening in tandem. And in some cases, one will happen more quickly than the other. I do think that we can’t, we can’t undersell the impact of public policy and laws that actually support childcare needs, paid leave, and maternal health as Chamber of mothers supports, because it’s just at the root, it’s at the root of everything, it’s completely interconnected. And when we solve that, for the mom who needs it the most, we essentially solve it for everyone. Because that woman is able to then show up for her family, raise the next generation to be productive, and also do great work at the same time. And it’s just, it’s a pleasure to be able to do it. But I think that what we need, we’re pretty far away from what we actually need. And yet, public approval on all of these things is through the roof. It’s in the 90s 90 to 98th, percentile, eight between 80s and 90s, depending on what what surveys you’re looking at, but the American public is ready for it, our lawmakers aren’t quite there yet. I think that private sector progress has really shifted cultural norms very, very positively in the right direction. And eventually, hopefully, soon we will elect people into office who are living, living the needs that they’re trying to solve. And we’ll get there.

Along those lines, you know, what would be some tips that you could share strategies, you could share it with working moms working dads in the trenches right now, who are looking for relief one day, whenever that may be, but in the moment, they have to deal and grapple with many of the things that you described having to grapple with? I know I did when I had my first child 26 years ago, a completely different landscape back then definitely, what can you say to them, to give them hope, and perhaps some, you know, some actionable tips that you can share?

I have seen so many times the power of one person speaking up. And I know it feels particularly if you’re asking for any kind of flexibility or accommodation, when you have a tiny baby, it feels like you’re negotiating with the highest stakes in mind. And for many, many women I talked to, it is the first time that they’ve actively negotiated for anything, and that can feel very, very daunting. What I found whether I’m coaching someone one on one, or speaking to a big audience of corporate managers, we’re trying to figure out how to get engaged in these conversations more effectively. The thing that unlocks people to have the bravery to do it, first of all is their kids kids are and we found this in the white paper I was telling you about earlier, the ROI of of caregiving benefits. Kids are motivators, kids are not to tractors, the reason people want to stay longer in their job, for stability sake, make more money for economic security move up in their career and find meaning in the work they do is because of their kids. So first of all, know that your kids are driving you and that’s a very good thing. Next, know that anything that you ask for any accommodation, or anything that stands out as something that’s different than what is normal in your in your team or your industry. Whatever we’re in your state is not just good for you, it feels like something you’re asking for because your daycare drop off is 15 minutes earlier than everyone else’s and doesn’t align with the weekly meeting, right? Super personal, very, very kind of vulnerable feeling. When you ask for that thing. There are other people around you who for one reason or another, cannot speak up to the same degree that you can, they may be marginalized or minoritized in some way that you’re not and they can’t take that small risk that you feel you can take it for them. You’re doing it for yourself, but you’re also doing it for everyone else around you who doesn’t have a voice that’s as loud that can feel I think, especially in the sort of awakening of nurturing that can happen for a lot of people in early parenthood that feels really motivating to but then further than that, also know you’re doing it for yourself. You’re doing it for your colleagues, you’re also doing it for your own employer you are actually doing your job well, when you show them the thing that you need to be able to still be here a year from now, to be able to be performing your best to be able to be working on a team where everyone feels good about each other’s personal lives and professional lives and works in synchronicity. It’s good for the greater economy, it’s there’s just the economic argument is there. So go do whatever you have to do to fill up your brain in your heart with all the research that you need to feel motivated and secure. And having those conversations come into any negotiation with not just not just the ask, but also really the plan. And you want to have all the answers, but you’re going to as the person who you can’t, we can’t solve problems we can’t see. So you’re the one who’s making it visible. But you’re also the one who’s going to have the most specific plan for how to address it. So come with that plan. And you’re actually doing the work for your manager in that way, as well come with a plan A come with Plan B, maybe come with a plan C and ask them to try it. If you get any kind of resistance, try it and keep track of your deliverables keep track of what it is that you’re trying to fulfill, to show that it can work, and then set a plan to reevaluate and see if it’s working fine solidarity, and not just any other brand new working mom, if that’s who you are, but also any colleagues who are doing care work that may not be as visible so I say all the time, like if you walk into a you know an office and they’re having you know, cupcakes for, you know, somebody’s baby shower, in the conference room, like that care need is really visible, if there’s a pregnant belly that it’s a very visible need. Even on a zoom like Ileen way back, you can see a belly, right? What’s not as visible as some of the care work that happens at later stages in life, which is research shows us largely largely handled by women. So it’s ongoing care for kids who have chronic conditions, you know, as they grow up, it is spousal care, it’s self care, it’s elder care, it’s your dad has needs chemo, and somebody has to take him once a week, and you go, they’re not always saying like, bye, guys and taking my dad to chemo, I wish they could. And when you speak up on behalf of new moms, you’re doing it for all of his other colleagues as well. And it becomes a universal need, not a niche need. And you’ll find solidarity there too. So as open as you can possibly be, please do. And I understand if if you feel like you can’t, but then try to link arms with a couple of other people so that you have that, um, that scaffolding around you to help you speak up for what you need.

One of the other interesting aspects of this whole conversation has to do with when women are having babies, and over the last 30 years dating back to 2019. In the preceding 30 years, more women in America, certainly somewhere upwards of 70% are having children between 35 and 39 years old, there’s certain things we can draw from that statistic, you know, more seasoned, experienced mothers becoming mothers for the first time. Does any of that, or has it had any impact on you and your work and your advocacy?

Yeah, you know, I think a lot of the moms I’m working with are coming from a position of being more, having more invested in the climb, you know, and not everyone is divines defines motivation in terms of climbing a corporate ladder, I don’t mean that necessarily at all. But they have a history to draw from, and they’re bringing that to their parenting actually, in ways that that’s really cool. And then they’re bringing their parenting to their to their middle management, let’s say or their management or to to their colleagues and skills that they’ve learned. So I’ve seen that. What I’ve seen also, though, is that, you know, a lot of the reason that people are waiting is because parents just incredibly expensive. Childcare has doubled over the last 20 years in terms of just its cost. And like I said, it’s just not that available to many people. Many people are able to afford a couple of days of real childcare, like paid for childcare and then are sort of cobbling together other ways. If they have a partner they’re working. And if swing shifts, they’re having maybe a neighbor, watch the kids in a more ad hoc fashion, which takes more management and takes more out of you frankly, just it’s just more sort of verticals to manage in terms of your kids care. And so that’s really stressful. So the women who I’m meeting, you know, in late motherhood in some ways, late starting their motherhood later are more share of sure of who they are, but then are more thrown when motherhood is harder than they imagined. And they’re starting later because they’re trying to save up for it. And unfortunately, they’re finding it’s just getting more expensive every year. So you may as well just go ahead and have those games. It’s tricky. They’re also having fewer kids though, and that ultimately is another really strong economic argument for this this support you know, we need to be able to have a sorry to be So just capitalistic about it. But in next generation of workers, we’re not going to have as many workers as we need to be able to support those who are aging now, if people aren’t able to have the number of children that they like to bring into the world because they can’t afford it.

Certainly lots to think about on a very important topic. Lauren Smith, Brody, author of the fifth trimester, CEO of the fifth trimester as well. Thank you so much for taking the time today.

Thank you Lianne.

[/et_pb_toggle]

As she continued to try and re-integrate into the workplace as a new mom, Smith Brody recalls making several surprising observations.

“At that point, I worked in women’s magazines, so largely with other women who were pretty comfortable talking about their physical needs emotional needs,” she says. “And yet I didn’t see anyone around me really talking about parenthood — it was very much in the sort of Girl-boss era of fake it till you make it, dress for the job you want not the job you have. Try, try try, just keep trying. And you’ll make it which of course didn’t account for a whole lot of factors that are much more systemic, which I didn’t realize at the time.”

For Smith-Brody who is a journalist, the key was to self-advocate.

“I found that the only way I could get through it really was by being very, very transparent about what was hard about the transition,” she says.

The experience propelled Smith Brody to chart a new course. That journey has included writing a book, The Fifth Trimester: The Working Mom’s Guide to Style, Sanity, and Success After Baby, co-founding an advocacy group called the Chamber of Mothers and a movement focused on supporting new mothers as they transition back into the workforce.

The “Fifth Trimester” and New Motherhood as a Developmental Stage

Brody’s concept of the “fifth trimester” draws from Dr. Harvey Karp’s notion of a “fourth trimester”—a period after birth when parents provide womb-like conditions to comfort newborns. In her book, Smith Brody expands this idea to encapsulate a critical phase for mothers as they return to work, viewing it as a developmental period of its own, not just for the baby but for the working mother adjusting to new physical, emotional, and logistical demands.

“I was in an executive position, surrounded by other women, and still I felt I had to hide the challenges of motherhood,” Smith Brody shared. When a coworker thanked her for being “real” about her struggles and still showing up, Smith Brody realized her transparency could be deeply impactful.

“I was in an executive position, surrounded by other women, and still I felt I had to hide the challenges of motherhood,” Smith Brody shared. When a coworker thanked her for being “real” about her struggles and still showing up, Smith Brody realized her transparency could be deeply impactful.

“…although working motherhood was new to me, and it was going to continue to be hard, what I had to learn from this point out was management and modelling and showing that we could integrate our real lives and our real personhood into work and still succeed,” she says.

Researching the Realities of Working Motherhood

In preparing The Fifth Trimester, Smith Brody conducted an extensive survey of over 700 women from diverse backgrounds and occupations to understand commonalities and pain points. A key insight was that women universally reported feeling more settled around six months postpartum, with mental health and physical well-being stabilizing. Unfortunately, this milestone comes long after the typical 12-week leave period covered by the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) in the United States, which doesn’t apply to nearly half of working Americans.

Smith Brody’s findings indicated a severe disconnect between corporate policy and biological needs. The mothers she surveyed reported that they needed at least six months to feel physically and mentally ready to reengage fully with work. “If you’re back before then, and it doesn’t feel right, it’s not your fault—it’s just that the system isn’t designed with parents in mind,” she says.

Pandemic-Driven Progress: A Shift in Perspective on Parenting and Policy

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the burdens parents—especially mothers—face when balancing caregiving with career responsibilities. It also sparked a broader societal conversation about the unpaid labour involved in childcare and household responsibilities, with families visibly shouldering these tasks while working from home. Terms like “unpaid labour” and “motherhood penalty” entered everyday vocabulary, leading to a collective realization that many women’s careers suffered when they were seen first as caregivers rather than as professionals.

“The pandemic put a spotlight on care work and brought terms like ‘benevolent discrimination’—when employers exclude mothers from career-building opportunities out of misplaced consideration—into the mainstream,” Smith Brody noted. With these conversations now more widespread, she feels we’re closer than ever to breaking down these stereotypes and building a supportive framework for working parents.

Economic Arguments for Parental Support

Smith Brody’s advocacy extends to demonstrating the economic benefits of caregiving support in the workplace. Her recent research partnership with childcare company Vivvi quantifies the return on investment (ROI) for caregiving benefits, showing that each dollar spent yields nearly $19 in increased productivity and output. This underscores that caregiving support isn’t just a moral imperative; it’s sound business.

“We now have the data to prove what we’ve always felt—supporting caregivers doesn’t just help them; it benefits the entire economy,” she says. Smith Brody hopes that economic arguments will push more companies to adopt policies that support employees in their caregiving roles, from flexible schedules to paid family leave.

“We now have the data to prove what we’ve always felt—supporting caregivers doesn’t just help them; it benefits the entire economy,” she says. Smith Brody hopes that economic arguments will push more companies to adopt policies that support employees in their caregiving roles, from flexible schedules to paid family leave.

Chamber of Mothers: Advocacy for Systemic Change

As co-founder of Chamber of Mothers, she collaborates with advocates to advance public policy for paid parental leave, affordable childcare, and maternal healthcare access. Smith Brody envisions a society where both public and private sectors work together to create structural support for caregivers.

“Public policy and private sector support must work in tandem,” says the mother of two. “We need paid leave, accessible childcare, and laws that protect maternal health. Supporting the working mothers who need it most will benefit all families,” Brody says, adding that 90 percent of Americans support parental leave, even if legislative change has been slow.

Practical Strategies for Working Parents

Smith Brody emphasizes the power of speaking up for support and flexibility as a strategy for navigating these challenges. While the prospect of negotiating workplace flexibility may seem daunting, Brody believes parents should feel empowered to advocate not only for themselves but also for their colleagues who may not be able to speak out.

“Your children are not distractions; they’re motivators. Request the support you need because it benefits you, your family, and the company’s success in the long term,” she said.

She advises employees to approach managers with specific plans, not just requests, showing how accommodations like flexible hours can benefit both the individual and the organization.

Smith Brody also encourages parents to find allies across different stages of caregiving. For example, a new mother and an employee caring for an aging parent may both need workplace flexibility for caregiving duties. Building solidarity within workplaces can lead to collective change and make it easier for individuals to voice their needs.

Related links:

Related articles:

Finding Balance Between Work And Family When You Work From Home

Science-backed Tips to Manage Working and Parenthood