[et_pb_section][et_pb_row][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text]

His lived experience, which began at a young age, serves as a searing reminder — of what he battled and survived — and underpins his deep desire to affect meaningful change in the lives of others.

[et_pb_toggle admin_label=”Click for video transcription” title=”Click for video transcription” open=”off” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

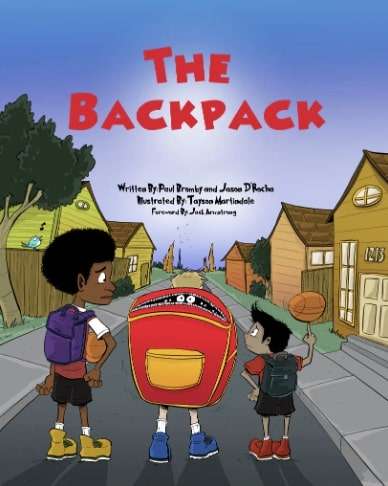

Welcome to where parents talk. My name is Lianne Castelino. Our guest today is a sports media professional. Paul bromby is a senior producer at sports net, and a professor at Centennial College. He’s also a youth basketball coach and author in the children’s literature space, and a father of one. His first book is called the backpack and focuses on kids and mental health. Paul joins us today from Toronto. Thank you so much for being here.

Thank you so much for having me.

It’s great to catch up after about 15 years.

It’s been a little bit for sure. Congratulations on venturing into the whole wild world of being an author. Let me ask you this poll as a starting point. What was the tipping point for you to decide to write this book?

That’s a great question. For me, I think the tipping point was I just had this desire and kind of burned in my stomach to do something creative, to help create awareness around mental health, tried to help end the stigma. I think I’ve been all very active and vocal about mental health on social media. But I felt like I wasn’t really in the fight. If that makes sense. I felt like you know, a lot of talk, but what are you going to do? What are you going to actually do to try to make a change and something substantial, that will outlive me, quite honestly. And so I also thought, What’s the best way to help, and I thought getting to the grassroots, and children are the grassroots. And if we can change the mindset and change kind of the perspective of children, then we can help, you know, solve this problem of mental health and stigma around it.

Still, it takes a fair amount of courage to decide to take something so intensely personal, that you lived, and then make it public.

Absolutely, I think if my mom was still alive, I don’t know if I’d be as able to open up about her struggles and our struggles, and my mom lived with bipolar disorder, from the time I was born until the time she passed. And if anybody has lived with bipolar disorder, or been have have a family member, it’s very difficult, it’s a roller coaster ride, it’s, it also has a huge effect on the people around them, I think we have a lot of compassion for the people that suffer through the oldest. But there is also a huge effect on the people that are in supporting roles within the family around them. And I know, you know, I’ve had to recognize this later in life, but my emotions often are, you know, affected by people around me, because I was so in tune with my mom, that I would try to hit make her happy or she was sad, I would get sad. And I had to recognize where a lot of these triggers and things were coming for me later on in life, it was my relationship with my mom, and how I would try to cheer her up and try to make her feel better and worry about her. And the worrying part is really what I tried to tackle in the backpack and that the backpack is a metaphor for the worries and burdens that I had as a child about my mom’s mental illness, and how you know, all children worry about something, my son, you know, 10 years old is worrying about a math test the other day, and I said, I promise you and the big picture in life. I know this seems really hard right now. But it’s not, you know, no matter how you do on this test, it’s going to be okay. And that’s just a small example. He plays basketball, he worries about you know, how he performs the different things like that. And I think, if I’m able to do anything is just to try to let children be children and have fun. You don’t have to have these big worries in your life. Let the adults do all the worrying.

Yeah, definitely. There’ll be plenty of time to worry down. Yeah.

Take us through that a little bit more, Paul, if you could, in terms of how old were you when you really truly understood what your mum was suffering.

I don’t think I ever have truly understood. I remember, as part of the eulogy, I had my mom’s funeral. And there was a lot of patients from the Nova Scotia hospital where she had been pretty much full time care there. And that’s similar to CAMH. Here in Toronto, it’s a mental health institute. And I said something along those lines that I truly never understood my mom’s illness and one of the patients during the eulogy yelled out it nobody understands. And it was it’s stuck with me. It’s always stuck with me that if this person who has suffered through their entire life doesn’t understand and us around us don’t completely understand. I think that’s also what creates the fear and the stigma around mental health is that we truly don’t understand why certain people suffer through it and why certain people, you know, can get themselves out of depression and funks and different things that they go through. So, I guess I The answer is I don’t understand, but I’m trying. And I think I became aware when I was about, I think six or seven that my mom wasn’t quite like other moms or dads that she was in the hospital quite a bit. She was always going to the doctors who was always taking medication. I could tell you 915 And nine I could tell you still because I would Reinder Have you taken your pill yet? Or pills yet your medication? And so yeah, that’s it’s fine that just popped in my head. But that’s still carrying, you know that how many years later. But I realized that it wasn’t quite normal like other and I use the word normal in quotations a lot, but it just wasn’t a normal upbringing, I didn’t have the same mom that everybody else did. And so I think I started feeling a little bit of embarrassment and shame and certain things that happened in public environments where people were laughing or judging. And I think it definitely affected me as a child. And I learned to kind of let go of it a bit, and not really until her passing

so much to unpack there. And I wonder if there’s a way for you to kind of answer the question about what would have been the hardest part for you as a child, when you look back on it in what was an obviously, such an all encompassing situation that you were dealing with, with your mom, and bipolar disorder. But if you were to pick out the most difficult part of your childhood coping with that, what was that have been the

most difficult part was that I couldn’t help her. I couldn’t fix her. And as a child, as a young boy, we really attach ourselves to our moms. And I see that my son, and I just felt like I just didn’t want her to be sick, I didn’t want her to suffer, I wanted to help her and just wanted to get her in the place or in I did see her be happy and have fun a lot of times in life, but I saw more of her struggles. And so for me, the hardest part was also feeling like it might be my fault. I don’t know why I had that as a child. But I thought that when she would get sick that I was causing her stress, or I was upsetting her, that would, you know, get her to the point where she would have a breakdown. And so I felt a lot of guilt, that it was my fault. And just truly didn’t understand it. And I know my mom really pushed for me to speak to somebody a professional. And also I had this wall up that if I spoke to somebody that would be like me admitting that I was sick, and I wasn’t sick. There’s no way I’m sick. I’m not like you. And so yeah, it really I mean that carried on into my adulthood, I wasn’t able to go speak to a professional until in my 40s. And my relationship with my son’s mom was falling apart. And a lot of it was a lot of the baggage that I had been carrying with from my relationship with my mom. And you know, it isn’t all my fault, but 5050. So but my 50 of it was a lot of on packed baggage. And really, my backpack was huge and heavy. And I’d carried it for far too long. And I think even people have said to me in the last little while since writing this book, I seem lighter and happier. And I do feel putting this story out into the world and knowing that it’s helping others has has lifted quite the guilt and burden off my shoulders.

You talk about your mum, having told you at that time that maybe you should go get help. Can you think of what would have helped you back then knowing what you know now.

After speaking to somebody speaking to a professional, it just allowed me to understand my emotions and feelings better. As a child, I had a lot of, you know, I was a rollercoaster I was happy, I was mad, I was sad, and didn’t have control over the emotion. So I think if I was able to speak to a professional and they could give me a perspective that it wasn’t my fault, that I also wasn’t the only child in the world that’s mom was sick, I didn’t see it. I didn’t know anybody that’s mom was going through what my mom was going through. And so I felt very alone and resentful that I had to go through this. And so a big part of writing this book for me is there might be a boy out there or a young girl out there whose family members going through this and they might be resentful towards them and they might not understand. So just being able to know that somebody else is going through it, I think is very helpful. It would help me it probably would have helped me grow a little better and, and be a little more comfortable with my mom’s illness than I was for a lot of my life. But hopefully, you know, with campaigns like Bell, let’s talk and other things like that, that the awareness is out there. And that we can understand that it’s obviously not their fault, and that a lot of people are going through this.

It is so difficult for adults to understand, as you’ve alluded to let alone kids, depending on what age of the child you’re talking about. When you think back on it, Paul, what was the greatest source of support for you to just survive every day and get to the next?

Well as an only child. That was another part that was really tough. And I had a dad in the picture who was also struggling and his. He used alcohol to numb his feelings and pain that he was going through. So it really for me and it ties right into the book Basketball, basketball and just having that passion on my hands to go outside and have that feeling of accomplishment of supportive teammates and friends. as, you know, as funny as it sounds, but that ball going through the net was like, you know, it was, it just made me feel great. And you know, I know that’s not the only part of basketball, but it really made me it built my confidence, I got pretty good at it because I practice a lot at it. And it just really helped me survive. It was my escape it was my sanctuary is my place to go when things were really bad. If there was a fight in the house, or, you know, my mom was having an episode, I would just go to the court shoot hoops for hours by myself or play against others. And it was my way to just release all of that negative energy I was holding on to.

thankfully, a lot has changed with respect to this society’s discourse around mental health. And it certainly as it relates to kids, what, you know, what would you like to see happening more with respect to where we are on this topic today? Because I think one of the things that you alluded to that keep in mind is we are talking about kids, if we’re talking about mental health in this particular example. And so, depending on their age, their level of understanding is going to be different. But what do you want to see happen with this topic in society as it relates to kids today?

I think, and you know, writing this book, I know, there’s going to be different opinions. And some people would think, Oh, this is too heavy a subject for children. I’ve had those comments to me. And that, you know, what’s the age group for this seems a little, you know, too serious or too heavy for younger children. But I think that’s exactly it. Like, why are we hiding it, it’s a, it’s something that happens. And so if we can start a conversation at an early age, I think the wheelhouse for this book, quite honestly, is about ages eight to 12. I think that’s where they really get it. But there’s some six and seven year olds that love the pictures, and they might understand it, when they get a little older and come back to the book, I would like to just see that we have these conversations and discussions. And my hope is that if a family is struggling, or a parent doesn’t really quite know how to explain it to a child that they’re struggling, that this book is a tool within the home within the school library, that people can use to start and have a conversation so children will understand a little better. And quite honestly, parents will understand that, you know, I had a meeting with this lady. And she’s become a great friend through it all. But she was really worried that she was messing up her child with her illness, and had a lot of guilt and hadn’t even had the conversation with her child about her illness. And her, her child was probably eight or nine years old. And after our meeting, like we both bawled her eyes out during this meeting, her name’s Yolanda, and I think she just saw me it was like, You know what, he’s fine, my kids gonna be fine. And I can be open and honest with her about what I’m going through. And, you know, knowing that you have that impact of people seeing your you know, and I don’t want to use overused status, but survival of going through these things that they can get through it as well. And you know, if I can be an example and show vulnerability and show that I got through it, that that really is my hope. I do think there is a space in in education and curriculums or education around mental health, whether it’s my book or someone else’s book, or even programs that are designed by professionals, I’m not a professional, I’m just an advocate and sharing my experience, but I really do hope that we, you know, end the stigma and really change how we view mental health and how we treat it.

Would you say that your journey living with a parent that had a mental mental illness shaped you as a person?

think I, you know, if people know me, as a friend, I try to make people laugh, I try to see the lighter side of things. But you know, there is also the the anger that they’ve seen the kind of the meats pulling away from people, I think it’s really, I’ve been, you know, a lot of part of my life, I’ve been a roller coaster, and I haven’t had the stability of, of, you know, being that person in it. That’s always I think you can rely on me, but I think my emotions have gotten away a lot of times. And so learning to accept those emotions and control them, has helped later in life. But I also think as a parent, it’s really helped me to know that I want to be the person that I needed when I was at age. So almost learn from the mistakes of my parents and I don’t want to use mistakes with things that didn’t work for me and try to do better. As a parent. I think if we, as all parents, I think if we tried to do that, I think our children will be in a better place. I also still think they’re going to resent us for something or they like why didn’t you do this? I know that that’s the reality. But you know, I’m gonna give my best I’m gonna try. I’m going to show up. I’m going to try and that’s really what’s the most important thing for me, kind of as a as a parent.

You talked about what the backpack symbolizes in you A book, I wonder what would your backpack have contained when you were a child

would have been a lot of worry. And I think as I got older, that worry turned into resentment and anger. And I think I was able to, I was able to take it off at some at some periods of my childhood. But again, basketball really gave me that outlet sports, football, baseball, I did track as well. So it wasn’t just basketball. I just happen to choose basketball later in life, but having male role models and coaches that really helped me with my emotions and speak to me. So yeah, my backpack would have been full of anger, resentment. And I see that when I coach like I see children, the young boys having meltdowns, getting mad, you know, getting upset about calls. And a lot of that stems from the fear of failure, a lot of it stems from feeling like they’re not good enough. And so I think I had a lot of that, and now I recognize it. And so I really tried to, you know, as much as I coach skills, I think I’m trying to coach life lessons is much, and those are as important or more important than how we play as a team, or how we put the basket or the ball in the basket. So I think being able to recognize some of my issues that I had as a child, and coaching now really helps me.

So along those lines, in all the multiple different roles that you do have father, coach, etc. What tools do you believe that a child today should have could have in their personal toolbox? If they have to, or you know, come into contact encounter somebody in their family or somebody else with a mental health challenge?

That’s a great question. No one’s asked me that yet. I think I really do think dialogue and conversation, I think a child being able to trust you as a parent, that they can have that conversation with you. And you know, about anything. And I think, you know, I remember when I was a kid, things that I was going through, I wouldn’t be able to talk to my parents about it, like things that I was going through outside, you know, peer pressure’s different things, you know, ages 1314 being offered drugs and alcohol. And I was, you know, if I could have gone to my parents and said, Hey, this is what’s going on, and I trusted that they wouldn’t get mad or upset at me, then I’d be more likely to go to them. So I think, you know, communication is huge, being able to not be afraid for them to come to us. I don’t think children should fear their parents, I think there should be respect. But I think a lot of our generation feared our parents, and I don’t necessarily think Yeah, they’ll probably keep you out of trouble. But I don’t think it’s eventually when you become an adult, those things are going to come to the surface. So I think communication is huge trust, trusting that the adults that you’re around whether they’re coaches, teachers, and and parents have your best intention in mind. So yeah, trust communication would be the two of the biggest ones for me.

Okay, can you take us through sort of your process for writing this book. So now you’re going through, you know, memories and things that you experienced your lived experience as a child you are venturing into now, putting this into words that young people can understand. I’m assuming that part of it may have been cathartic for you? Like what was the process that you undertook to write the backpack?

Yeah, I think when I had the first idea of it, it was very junior. It was nursery rhyme. And I think that was my way of starting the process, and even the story itself. Jason DeRosa, who is started his own publishing company, Junior storytellers, helped me co author this and really helped me build the story. And because I knew what I wanted to, you know, what I wanted to accomplish with it. And I knew some of the parts of the story, actually pictured it in the images and illustrations that taste and Martin Dale did, more so than the words. So I pictured it as this big heavy backpack, it was always red in my mind, and I carrying it around, and I pictured these, you know, animals and being very animated when he would get upset or stressed. And so then it was to think take examples from my childhood, like my mom coming to a game and walking across the middle of a court and a game and different things that embarrassed me as a child and trying to build a story around it. That Jason I had these conversations, he said, You know, when I saw my parents in the stands, like, yes, my mom’s there, my dad’s there. For me, it was like, Oh, my God, don’t embarrass me. And then I started playing terribly or let it affect me. And big time telling him like this your experience, like he wrote a book called my mom, my superhero, great book. That wasn’t my experience. So I wanted to share and I love my mom and as much as he loved his mom, it was just different. So I really just wanted to tell my story and that others could relate to hopefully, but really was I started, I think the first night, I had a glass of wine and started writing, and I’m not a wine drinker. But I felt like that was the right thing to drink. To get my thoughts out there, and it really did help it, I sent him this long email of all kinds of thoughts and different things of the story. And then we would meet at the library every probably, you know, every week or two, and just have a creative session where we flush it out. And there was a lot of moments where, you know, he, I would say something, and then he would say something back would be like, Oh, it was like, just that really cool, creative energy. And it was like, that’s amazing. And, you know, and so that was really cool. And we really connected. And it was, it was a very easy process. After that once we kind of built this story. And he also has a degree in child psychology, which helps, I was very worried about the wording not being right. I didn’t want to be offensive or upset people in the mental health community, because, you know, I personally am not suffering through it. I’m an advocate, but I wanted the message in the wording to be proper. And I think we have hit that. And most people, you know, haven’t heard anything otherwise. So, yeah, it really took five years. I think you’ll understand this, when you watch TV, it’s like, Oh, that can’t be too difficult. But when you make TV, it is very difficult. And so the same with a children’s book, you’ve read it. And yeah, it’s 24 pages, it seems like a short book. But that was five years of work and going back and forth. That took a lot of time. And hopefully, the feedbacks been amazing. And hopefully, it’s delivered the message that we were hoping to deliver.

I want to pick up on the example that you shared about your mom and mom walking across the basketball court. How did you explain that to people around you? And I’m assuming there were other examples like that, as a young boy, how do you go about explaining that to kids, in your friends around you?

Quite a few examples, I can think of one where my Mom promised me and my friends that she would take us swimming at the lake, but we didn’t have a car. And so then the parent who had to take us to the lake was really angry, because now whatever she had going on in her life, and she had to, you know, change her plans, because there’s a bunch of kids expecting to go swimming. I got stung by a bee one time, she tried to cheer me up and took me to a Chinese food restaurant, we ate but then she didn’t have money to pay. So now I’m sitting there, and they’re upset at us. So those examples, I mean, we couldn’t really tie it into the book. But those are core memories, the shame and embarrassment that I felt was really hard to let go. I think now I almost look back at it and have a giggle about it. Like she bought, when I was in university, she bought me a pair of snowpants for my birthday, which is in June 15. My friends and I had a laugh about it. But there was still that, you know, still that kind of like the awkward feeling. But I think the fact that I could laugh at it sometimes really helped. I think I had a group of friends, maybe three or four that really were in my inner circle that I could trust and tell them about it. Those were also the friends when we got older that had cars would help me get my mom to the emergency room when she was having a crisis. At two or three in the morning, sometimes calling your friend’s house stainless, I just need your help. I know I might need to get a cab and gotta get my mom to the hospital. So it was difficult to be open about it quite honestly, it’s not difficult now because you know, I just feel like I’ve dealt with it, I’ve come to grips with what it was, but as a child and seeing other parents and how they interact with their kids, even the simple conversations that I have with my son now. I was more of a parent to my mom that my mom was apparent to me. And that relationship made things very complicated. So yeah, there’s just so much to it a lot to unpack as you get older and understanding why certain things are triggers for you why it’s difficult. And you know, even being vulnerable, vulnerable about these things to me is healing. And I think with, you know, with leadership, vulnerability is a big component to it. Because people want to feel like they can relate to you. They want to understand your story. And I think understanding your story will help others.

Along those lines, you spent much of your life and career around sports amateur professional excetera. Are there any particular examples of athletes who’ve come out and shared their own personal lived experience with mental illness, whether it’s themselves or their families that has impacted you moved you deeply?

Yeah, I think I could think of three. Bobby Ryan, a hockey player. He was with Anaheim and the Ottawa Senators and he had a very tumultuous upbringing with domestic violence. And then Kevin Love and DeMar DeRozan in the NBA recently have come out and spoken about spoken about their mental health and the pressure of playing in games and tomorrow started his own podcast recently, and being very open about it. And to me, that is leadership. And that’s what I was talking about showing your own vulnerability, then I can guarantee there’s hundreds, if not 1000s of more professional athletes that have those same feelings, but are afraid to open up about it. And we see a lot of, you know, suicide and males older, a lot of CTE, like brain trauma from different sports that you know, haven’t been properly diagnosed or deal dealt with. And I do think of professional sports and being around it, you can see it, you know, it’s really tough. But if athletes like Damar, and Kevin, come out and speak about it, then maybe others will and get the help that they need before it becomes too late.

Part of the conversation and think that we need to allude to here when we talk about this topic is how boys are raised as well. Right? So as a father to a son, in what ways would you say that your lived experience, the whole experience of writing this book, reliving some of that has impacted how you parent?

That’s a great question. Because I think if I had had my I had my son in my early 40s, and I think if I had had him in my 30s, I probably wouldn’t have been the parent, like, toughen up, suck it up, you know, you’re all right. Because I had to get through by being tough, like I had to, you know, play basketball was a very competitive, tough sport playing football. So I had to suck it up and be tough to get through. But I also think there’s space to embrace your emotions and understand that you don’t always have to suck it up, like you can actually break down and BLP vulnerable and cry and talk about things. I think, as a parent, now, I tried to have those conversations, you know, on the way to the games and practices. It was a great Jack Armstrong to read the foreword to this book talks about shoulder conversations, shoulder talk, when you’re in the car, you’re side by side, or he’s behind you. And there’s no tablets or phones as distractions, you turn the radio down a little bit, and you have an open conversation. And it’s amazing the things that my son will say to me in the car, that he probably wouldn’t say to me, if we were sitting, you know, across each other at a table, like it just it feels a little less personally, I don’t wanna say less personal, but less like, I’m your dad, you know what I mean? So we have great conversations in the car. And we I always ask him about his feelings and emotions. You know, why? Why do you seem like you’re nervous in that game? Why are you nervous, and don’t be afraid to make mistakes, all the things that nobody really told me until I got older, are the conversations that I tried to have. I think we have changed as a society, I think it’s okay for men to embrace their feelings and be open and talk about them. Not quite as much as we still have work to do. But I do believe I try, you know, try to parent with empathy and understanding and let him be emotional. And yeah, that’s fine. I’m not gonna let him throw a temper tantrum at the mall, if he doesn’t get something but, but there’s, there’s ways that you know, if he’s emotional upset that I can, you know, relate to him and speak to him. Well,

is there a piece of feedback in particular about the book that has struck you?

Yeah, I’ll try not to cry. So I did the first and the whole process with Jason, I would be in the library. And he reminded me this afterwards, because I really didn’t. But I said, you know, I could picture us going into a school. And let us do those old gymnasiums and having a bunch of kids sitting on the floor and taught and reading the book to them, and then answering questions. And so one of the parents of the boys on my basketball team, she works in the Toronto District School Board, so she brought me into military trails Scarborough. So we did a morning reading. So the first session, we did nine to 10, there was 100 children in the gym, from JK to grade six. And they were really engaged. It was really cool. Jason does some stuff where they can spin the basketball and put it on the kids fingers. So they were really into it. But when the when he started doing the book reading, and I was standing there and I could just like it was very quiet, everyone was engaged. And then we got into questions. And this one little boy stood up who was seven years old, and put his hand up and he said, his name was Carson. He said, My mom also has mental mental illness, and I worry about her. And it shook me to the core, because, you know, I was just like, Oh man, that’s literally like me looking across at my seven year old self. And so you know, I first of all thanked him for standing up and being so brave to be open about it. And then really just tried to give him the message eyes and be okay. And I was like, look at me and I’m big six, seven, big guy here. I’ve got through it, you’re gonna grow to be big and strong yourself. And I don’t know why I was pointing out the physical appearance of myself but I just wanted him to have confidence that he’s gonna get through this and and so I really hammered home the point of that it’s not his. It’s not his job to worry right now. It’s his job to be a child. Have fun, play, learn at school, and that’s it and whether that message got through I hope it did. But And Jason afterwards gifted him a book and we signed it to him. So hopefully, at some point, you know, in his life that he’ll understand that he’s not alone. He’s not the only one to go through this and that I went through it and I’m fine. Fine, I’m okay. But he’s gonna be fine as well. And when we’re in when we’re, I did get choked up at the start of it, but we, when we came out of the school changes, like that was unbelievable dude, like you manifested that moment of this one child, you know, that we spoke about all these times in the library. And I was like, yeah, and then I got in the car and had a complete meltdown. At that point, I was able to release those emotions. And, you know, just felt like I just spoke to my seven year old self, so it was really rewarding. I know, I’ve gotten messages from other kids videos and text messages from parents and how much it’s helped them explain their situation to their children. So, yeah, it’s been incredibly rewarding. Teacher saying this should be in every school curriculum across Canada. Comments like that to me, you know, whether it is or not, at least I know it’s connected with one or two people.

Oh, I’m afraid we’re out of time. But thank you so much for taking the time. Paul bromby, author of The Backpack, thanks again.

Thank you

[/et_pb_toggle]

“I’ve been very active and vocal about mental health on social media,” says Paul Bromby, a sports media professional and father. “But I felt like I wasn’t really in the fight. I felt like [there was] a lot of talk, but what are you going to do, what are you going to actually do to try to make a change?”

That self-reflection moved him to action.

“I just had this desire kind of burned in my stomach to do something creative, to help create awareness around mental health, try to help end the stigma,” Bromby told Lianne Castelino during an interview for Where Parents Talk.

“What’s the best way to help, and I thought getting to the grassroots, and children are the grassroots. If we can change the mindset and the perspective of children, then we can help solve this problem of mental health and stigma around it.”

Mental Health Through a Child’s Eyes

Bromby, a Producer at Sportsnet and a youth basketball coach, endured what could at best be described as a challenging childhood. “My mom lived with bipolar disorder from the time I was born until she passed away,” he shared. “And if anybody has lived with bipolar disorder, or have a family member [with it], it’s very difficult. It was a rollercoaster ride—a constant state of worry for her and for me.”

That relentless strain he experienced as a young boy marked him then and since.

“I’ve had to recognize this later in life, but my emotions often are affected by people around me, because I was so in tune with my mom that I would try to hit make her happy,” Bromby says.

“I’ve had to recognize this later in life, but my emotions often are affected by people around me, because I was so in tune with my mom that I would try to hit make her happy,” Bromby says.

“If she was sad, I would get sad. And I had to recognize where a lot of these triggers and things were coming for me later on in life.”

Enter The Backpack — the creative pursuit that made Bromby an author.

“The Backpack is a metaphor for the worries and burdens that I had as a child about my mom’s mental illness, and how all children worry about something.”

He draws on personal memories, such as reminding his mother to take her medication or trying to soothe her during difficult moments, to illustrate how children often take on responsibilities that are far too heavy for their age.

The Backpack is also a story of hope, a tool designed for parents and children alike to better understand and discuss the complexities of mental health. “My goal is to let children be children,” Bromby says. “They shouldn’t carry these huge worries in life. Let the adults do the worrying.”

The Challenges of Growing Up

Looking back on his childhood, Bromby, who is the father of a 10-year-old son, admits to never fully understanding his mother’s illness, and even now, some aspects remain unclear.

He recounts a powerful moment during his mother’s funeral that highlighted this sentiment when a patient from the mental health institute where she received care stood up and shouted, “Nobody understands!” The lack of understanding, Bromby believes, is part of what perpetuates the fear and stigma surrounding mental health.

When asked about the hardest part of his childhood, Bromby doesn’t hesitate. “The most difficult part was feeling like I couldn’t help her,” he said. As a young boy, he felt guilty, often believing he was to blame for his mother’s breakdowns. “I thought I was causing her stress,” he shared, “which was a heavy burden to carry.”

Despite the challenges, Bromby found solace in basketball—a sport that became his escape and his sanctuary. “Basketball gave me a sense of accomplishment and confidence,” he explained. “It was my release from all the negative energy I was carrying.”

Turning Pain Into Purpose

Writing The Backpack was cathartic for Bromby, offering him a way to unburden the emotional weight he had carried for so long. “People have told me I seem lighter and happier now,” he says. “I do feel like sharing this story has lifted some of the guilt and burden off my shoulders.”

Bromby is not just telling his story for soley personal healing; he hopes his book will be a tool for children and families going through similar struggles. He acknowledges that some people might think the topic of mental illness is too heavy for children, but he counters that hiding these issues does more harm than good. “Why are we hiding it?” he asked. “If we can start conversations at an early age, we can help children understand.”

Bromby is not just telling his story for soley personal healing; he hopes his book will be a tool for children and families going through similar struggles. He acknowledges that some people might think the topic of mental illness is too heavy for children, but he counters that hiding these issues does more harm than good. “Why are we hiding it?” he asked. “If we can start conversations at an early age, we can help children understand.”

The Importance of Dialogue and Support

As a parent and youth basketball coach, Bromby believes communication and trust are essential tools that children need when dealing with mental health challenges—whether their own or those of someone close to them. “Children need to feel safe coming to their parents or other trusted adults about anything,” he said. “They shouldn’t fear their parents. There should be respect, but not fear.”

This mindset has influenced how he approaches his roles as a coach and father. “I try to coach life lessons as much as I coach basketball skills,” he explained. “I recognize a lot of the emotions I had as a child in the boys I coach—anger, fear of failure, and feeling like they’re not good enough.”

A Hope for the Future

As society’s conversation around mental health continues to evolve, Bromby hopes his book will contribute to further de-stigmatizing mental illness and encouraging open conversations, especially among young people. “If I can show vulnerability and help others feel like they’re not alone, that’s my goal,” he says. Bromby also envisions a space in education for mental health literacy, particularly as it pertains to children, to help families and educators navigate this critical topic.

Ultimately, The Backpack is a book for children, a reflection of Bromby’s lived experience, a story of resilience and hope, and an invitation for others to engage in the conversation around mental health—starting with the youngest among us.

Related links

Related articles

Navigating Your Child’s Mental Health

Mental Health Fitness Strategies

Parenting Through Youth Mental Health Challenges

Independence and Youth Mental Health: Study

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]